My Alaskan Summer (2008)

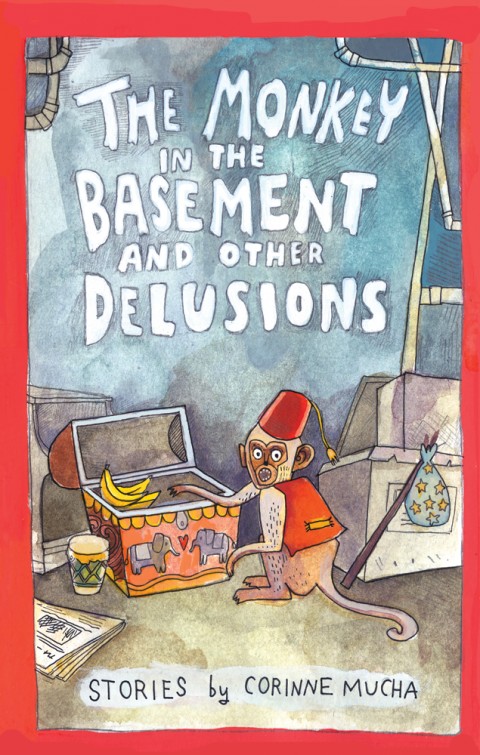

Corinne Mucha is a cartoonist with a unique gift for storytelling. Her sense of humor and insightful observations about human nature quickly garnered her work a level of attention uncommon among alternative cartoonists. She is the recipient of a Xerix grant for My Alaskan Summer and an Ignatz Award for The Monkey in the Basement. Her latest book, Get Over It, was published in June by Secret Acres.

In addition to all the comics she draws, she teaches art classes at MCA and the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago.

Festival Season spoke with Corinne about comics as a creative outlet, the value of art as play, and how stories help us shape our identities.

![]()

Festival Season: When did you start seeing yourself as an artist? Is it an identity you always had or did it come to you later on?

Corinne Mucha: I started saying that I wanted to be an artist when I was a kid. My parents tell me it was when I was four or so. Luckily, they took me really seriously. They said, “You want to be an artist? Great! We’re going to enroll you in all these extra-curricular classes because if this is what you want to do with your life, then you’re going to work hard at this and get better.” So I knew growing up that that’s what I wanted to do. After high school, I enrolled in the Illustration program at RISD.

During my Junior year at RISD, I was doing a study abroad program in Rome. It was independent study so we could do whatever we wanted art-wise for the whole school year and still get credit for it. It was an amazing opportunity. I was making watercolor paintings and collages and continuing some of the work that I’d been doing in Providence. Then I wanted a way to keep track of whatever I was doing during my day. So I started keeping a comics diary, but that’s not what I was calling it when I started it. To me, they were just notebooks full of pictures and words, like an illustrated diary. It was some of my classmates who encouraged me to call them comics.

“You wait for somebody to hand you your first check and the memo on the check says: ‘You are a REAL artist now!’ I think that’s the moment we all hope for.”

When I went back to school the next year, I took a comics class taught by David Mazzucchelli. That’s when I started getting serious about it. I think that with being a writer or being an artist in general, there is this sense that something has to happen for you to be legitimate and it has to be something external as opposed to internal. You wait for somebody to hand you your first check and the memo on the check says: “You are a REAL artist now!” I think that’s the moment that we all hope for. I don’t really know at what point I started to feel I could call myself a cartoonist. Or when people asked, “What do you do?” I could say I’m an artist instead of listing off whatever odd jobs actually paid my bills at the time.

FS: Do you have a sense of who your audience is or who you’re trying to connect with?

CM: The people I’m thinking of first are my friends. There’s maybe a small group of people that I know, whose opinions I really value, and I show them work before I show anyone else. And then I think it’s surprising that other people do read it. (laughs)

And then whether I mean to or not, I think of my mom a lot. She’s read everything I’ve written and is currently selling my books to everyone she knows as if they are girl scout cookies. It’s really sweet. Because of that, I tend to keep my work a little PG then I might otherwise. Still, at this point it’s more of a handful of people I think of. And I think, “This person will definitely read it because I will MAKE them.”

FS: Sounds like a captive audience. But some of the comics in your Buzz series definitely have jokes that also feel universal – new coffee drinks, for example, or breakfast shortcuts no one is taking.

CM: Those kinds of comics usually come from something I’m doing in my day. My brain is constantly brainstorming new options. Like, “All right, I’m drinking coffee right now, what are some other coffee drinks you could invent?” I only end up writing those things down maybe 15-20% of the time. I’m not really that great about writing down everything that comes into my head. This part of the way my brain works never really found a home until I started making comics.

Buzz #4 (2012)

FS: Going back to the sketchbooks you were been keeping in Rome – you called them diaries. When you were working on them, were you thinking that they were for your eyes only? A diary sounds really private to me.

CM: I definitely didn’t include super personal details of my life. They were more the kind of thing that was like- this what I did today, and then this is a bunch of stuff that I thought about. Stories about drinking too much coffee, or stuff that I daydreamed about in art history classes. A lot of imaginings about inanimate objects coming alive. Or stories about trash picking and imagining genies coming out of the trash that granted us wishes. And a lot about travelling, too.

I had to present them in critique because we had to show everything we were working on. But it was a really small program; there were only thirty of us. So I was kind of forced to show them to people, which caused me to censor it automatically because I knew I had to give the comics to an audience of some kind. (laughs) Then I was spending so much time doing them that some of my friends started asking me, “All right, what did you draw today?” Especially when they knew we just had some adventure together.

At the end of the year, I didn’t make a minicomic because I didn’t know what a minicomic was then, but I photocopied my whole sketchbook and I gave it to anyone in the program who wanted one. I guess that was my first experience of taking something that was really private or semi-private and publishing it in some sense.

“This part of the way my brain works never really found a home until I started making comics.”

FS: It sounds like the initial feedback you got was so positive. It must have been really encouraging.

CM: Yeah, I don’t know where I would be now if I hadn’t gotten so much encouragement in the beginning. When I look back on those comics, they’re almost illegible. (laughs) I’m really not exaggerating. I have no idea what those people saw in them or how they were physically able to read them. Because there’s no panel borders or anything – it’s all just basically scribbles and then some kind of picture and then word balloons. And there’s fifteen individual pictures/ paragraphs on a page, and then I’d always run out of room, so I’d just cram things into the bottom when I couldn’t fit it.

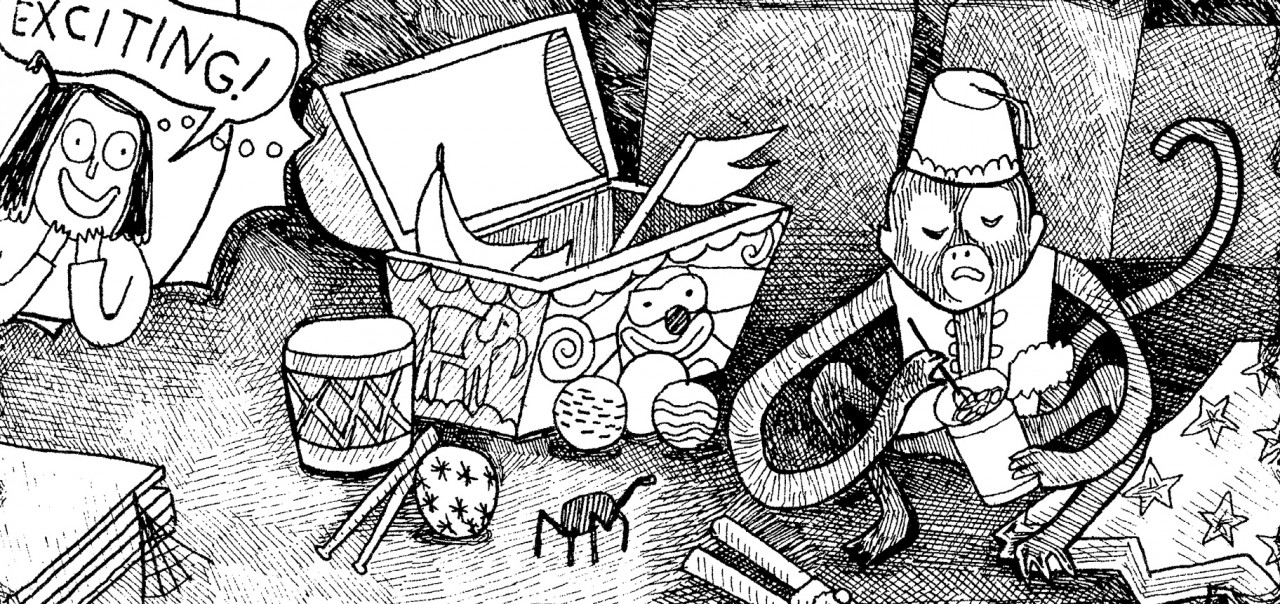

Recent Work (2007)

Also, it took me a really long time to learn how to draw from my head because I was very used to drawing from life. I’d gotten pretty good at copying at that point. But that muscle is a totally different drawing muscle, I think – the one where you think of something and then you make it appear on paper. And I was very bad at that. So not only was my handwriting basically scribbles, the drawings were essentially just glorified stick figures. Nobody had any bones at all. All the characters kind of looked alike.

It took me such a long time to finally put two and two together and say, “Wait a minute – this is how I can use reference photos! Because I DO know how to draw something I’m looking at and combine it with something I’m thinking of in my head!” But I had been drawing comics for a while before I think that finally started to come together. I’m still working on it.

FS: You’ve now been teaching comics and art for a while. Is that how you are able to continue to keep it a daily practice?

CM: I knew when I was in school that I wanted to be involved in education somehow. I’ve always really enjoyed working with children. But I didn’t want to be a full-time teacher, so I’ve gone the Teaching Artist route instead. I’ve been really lucky to have found some jobs in Chicago where I get to focus on comics, although it’s not what I do exclusively as a Teaching Artist. I also teach topics in contemporary art, and that sometimes involves comics but a lot of times involves conceptual art.

There’s certainly a relationship between my practice as an artist and my practice as a teacher. It’s really fun to spend time with kids, trying to encourage them to get their ideas down on paper. It can be inspiring to watch them struggle, or try to learn a new drawing skill. Or sometimes they are like, “Oh yeah, I’ve got a GREAT idea!” Then they finish it in five seconds and they’re like, “Read this!” and it’s, well… it makes no sense, but that kid is SO happy right now!

Then the question is- “How can I hold onto that same art-making spirit my studio practice?” Because as adult artists, we get so frustrated with ourselves when we make things that aren’t as good as they were in our heads. It’s not every child, but to watch some of them just shamelessly be like, “Yep, MADE IT! This is a poop comic, all of the shapes look exactly alike, and you can’t read a single word I wrote on here, but please show it to everyone that you know – it’s a masterpiece!” That’s amazing.

FS: It’s real confidence, just from the act of creation. It seems like an important part of enjoying or creating art is making a space that values play.

CM: For sure. I value just being able to ask “what if?” in my work, in any kind of way. I pose that question to kids: What if that zombie you just drew went to the moon? Or what if he went to the desert, what would happen? In my own work, asking myself questions like, what if that teapot in my kitchen came alive? How would that change my day? Those are the kinds of questions that interest me. A lot of that is about play. I’m trying to find an intersection between the real things in the world that have some value or beauty, and imaginary things, and then amplify that. How can I add value to this thing that I already find interesting? Maybe look at it in a new angle and tell stories about it, or just try to emphasize something new about it.

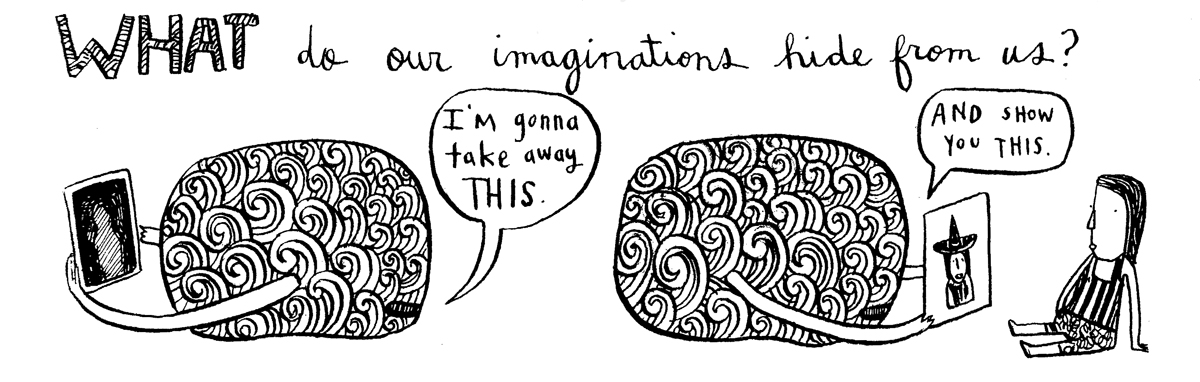

FS: “What if?” is a wonderful question that you could bring to so many different scenarios. Are there other questions that you feel you’re constantly, maybe not even consciously, returning to again and again in your work?

CM: It depends on what kind of comic I’m working on. If I’m using something that happens in real life as a starting place, something that’s more like a memoir comic, like Get Over It, then what I’m usually asking is “How I can take this thing that happened and then treat it almost like a found object? How can I take that thing and then transform it into something new? It’s like if you found a cardboard box in an alley and you decided to turn that cardboard box into a robot. There are certain things about the box that you would keep, maybe because you want to maintain the integrity of the cardboard, or the box-iness of that box. But there’s aspects of it that you would toss, and there are other parts you would add onto. You would probably draw eyes on it, or robot teeth, or something. So with personal work, the question I’m asking is- “How can I take something real and then change it to add meaning to it?” I want to use personal storytelling to either try to understand my own experience better or to try to use that experience to talk about a bigger idea.

“What if that teapot in my kitchen came alive? How would that change my day? Those are the kinds of questions that interest me.”

I’ve been writing more fiction recently where I start off with personal experience. Maybe I don’t want to write a truthful comic about that experience, so instead I try to find a really dramatic way to fictionalize it. Or I try to find a new angle to consider something that I’ve been thinking about a lot. I’m a really obsessive thinker. And I am always trying to find ways to break out of that because it’s not always the best habit. Recently I’ve been writing more fictional stories about women who have really bizarre obsessive habits. Like a woman who becomes obsessed with the idea of good hair days or someone who becomes obsessed with idioms and figurative language and trying to figure out the meaning behind them. Maybe those aren’t exactly questions, but I think those are the starting off places for some of my work recently.

The Good Hair Day Scientist (2014)

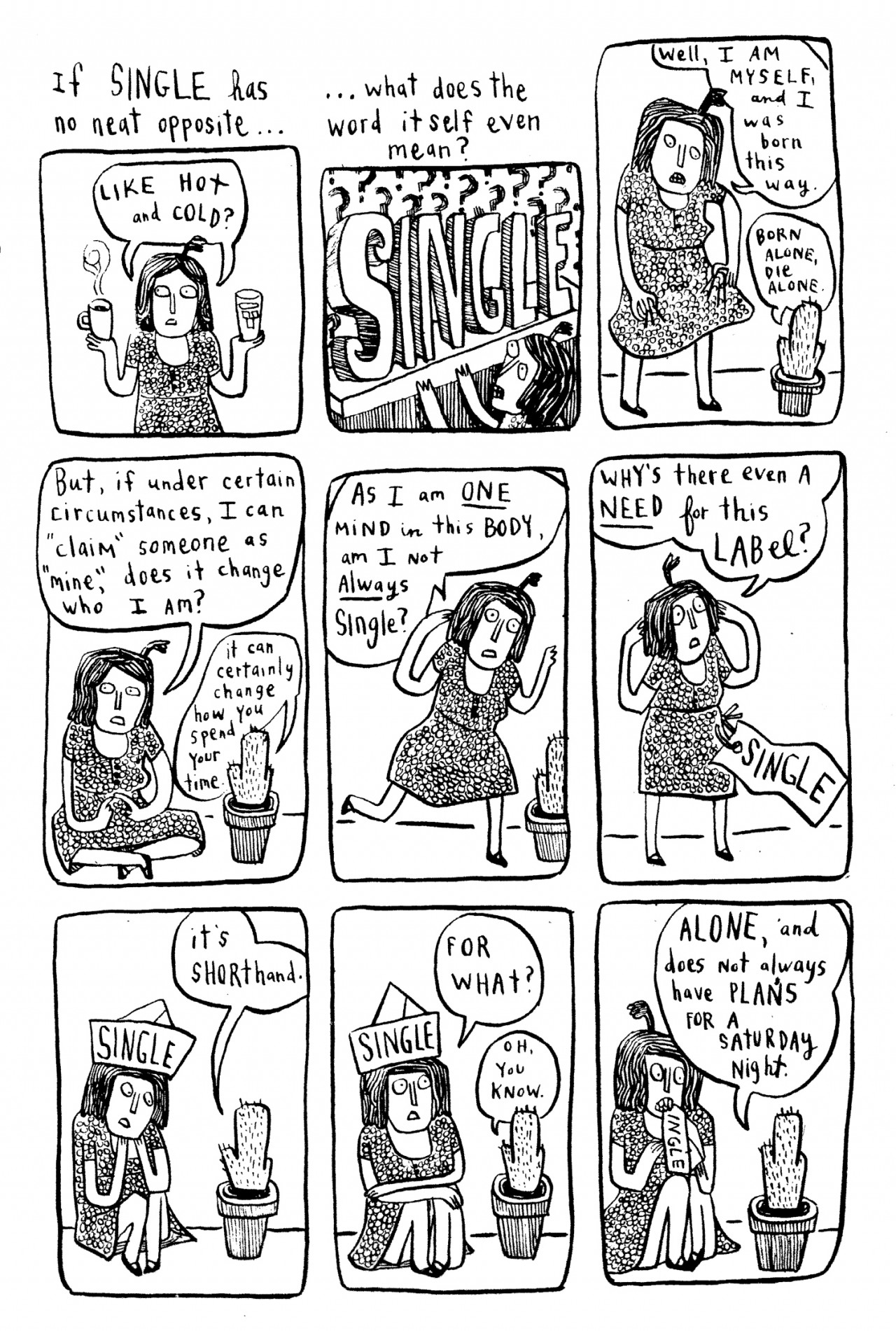

FS: You pose some interesting questions in My Every Single Thought: What does it mean to be single? What is the significance of this label? Why does it matter? So much of this really has to do with female experience and female thinking, and the way that society thinks about females. Do you consider yourself a feminist?

CM: I definitely consider myself a feminist. When I’m approaching a certain personal experience, I can’t help but have a feminist perspective on it. I am really interested in labeling and in particular the ways that women might be seen as archetypes or stereotypes – that fiction that we as a society create which affects us in real ways personally. In any aspect of the human experience, we create bigger narratives to try to make things simpler. Ultimately that ends up being limiting or restricting, and people sometimes have to fight to get out of the boxes that they’re put into. One of the reasons I started working on the Single comic was because after that breakup, I was newly struck by how odd the label of “single” is. I had this new label that, as someone in their mid-twenties, had all of these negative associations with it. And I was like, “Wait a minute, this is bullshit! Why do I feel bad about this? This is totally a meaningless word! Let me try to pick apart the ways that this is a meaningless word, and think about why we might ascribe so much value to it.

My Every Single Thought (2009)

FS: Your contribution to The Big Feminist BUT anthology, “Am I a Spinster Yet?” has such a good ending. You talk about how the label originally defined a spinster as a creative woman who really puts in all of this time and all of this energy to make something completely unique and completely her own, which sounds very empowering.

CM: I think that’s an example of a really funny way that labeling’s gotten so mixed up. It’s pretty bad-ass to actually be a spinster, especially in today’s society. It’s the ultimate DIY! You took wool from an animal, and you spun it into something that you actually make fabric out of? That’s crazy! But we’ve given it this dual meaning, and taken something that’s so positive and turned it into something which we assume is negative, even though there’s not a reason that it should be.

FS: When you take real experiences and turn them into fiction, is there a certain amount of real world material that has to stay? Or do you feel like you can, like you said, take a teapot and leap off into the most fun place with it?

CM: For fiction to be effective, it can be as magical or unrealistic as you want, but it still has to have something that anchors us to our everyday experience. So that even if we haven’t experienced that thing in our life personally, we can still relate to it.

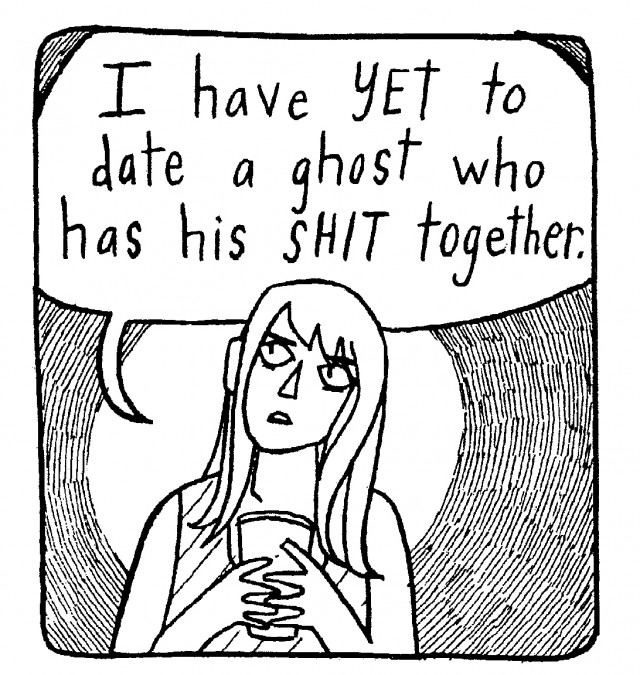

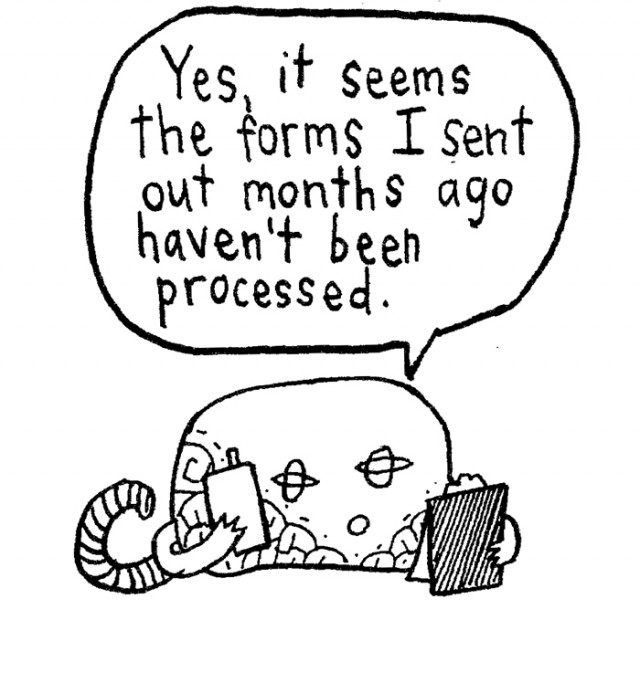

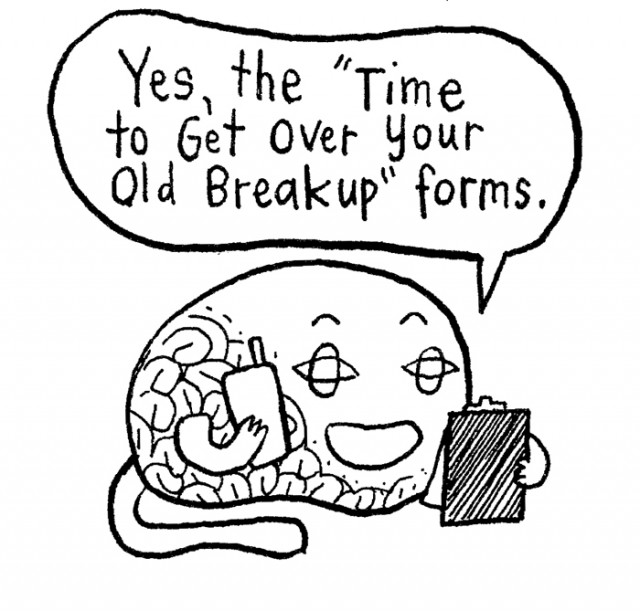

The Girl Who Was Mostly Attracted to Ghosts (2013)

FS: Would you say that emotion is that connective tissue?

CM: Yeah. A common emotion could be the thing that anchors fiction to our world. Or just experiences that aren’t real but still seem possible. You find some aspect of that experience that you do on a daily basis. I don’t know that any of the fiction that I write is really that out there. I have stories about imaginary buildings and ghosts and that kind of thing, but they’re still about regular people. I don’t deal a whole lot with elves and fairies.

FS: Let’s talk about the common emotion in Get Over It . Even though readers didn’t have this relationship, there is so much of it that feels universal. There’s something compassionate in the way you handle the material and create space for readers to respond to it.

CM: One thing that’s been surprising to me is how many people have said, “Oh yeah, I can totally relate to that breakup. I didn’t have exactly the same thing but I’ve totally been there. I understand what you’re saying.” Because when that’s happening in your life, you feel a little bit crazy. It feels like such an original experience that you’re having. It’s like- “This has NEVER happened to anyone else before! I invented this feeling and it’s terrible! And yet! I don’t know how to make it stop!” It’s funny because that book is about something that happened a lot of years ago, so I’m like, “Where were all you people when I was going through this?” I felt like it was this pathetically unique experience at the time, but maybe that’s part of wallowing in self-pity. Everybody feels that way. This book is definitely the most personal thing I’ve ever published. I took more risks than I have in the past in order to be more honest and to really say what I was thinking. There were a lot of stages in the editing process where I was like, “Huh, for this story to work I’m gonna have to admit this personal thing, and I don’t really want to admit that thing, but okay, here goes!” So I’m really grateful that so far it’s been really positively received.

FS: You write about the importance of being mindful and embracing a lot of the pain or the negative thoughts rather than stuffing them. It reminded me of some meditation and yoga practices that help get you comfortable with discomfort. I wonder if you have a daily practice like that, and if you think it has informed your work.

CM: Both of those things have been a part of my life for a pretty long time. I’ve been practicing yoga on and off for twelve or thirteen years. I still can’t touch my toes without bending my knees! (laughs) I’m just not a very flexible person, I might never be and that’s fine. But those practices do have an influence on my daily life, so I think they have an influence on my work as well – this book in particular and this experience in my life. I first tried the usual route after this thing happened that I didn’t want to happen, and said “Well, time heals all wounds, I’ll just wait for this to pass by and then I won’t think about it anymore and I won’t have any feelings ever again! I really look forward to that day!” But that didn’t happen, and then it just kept hurting past the arbitrary deadline I’d created. I think we all do this to some extent – we say “You’re allowed to feel this thing, but you are only allowed to feel it for this period of time and when you feel it past this period of time, it’s no longer acceptable. And when you’re doing something that isn’t acceptable, then you’re a failure.” So we add insult to injury.

I got to a point in processing that breakup where I was just desperate to try something new to not feel so bad anymore. And the thing that I finally learned was that when we push away uncomfortable feelings, that resistance actually gives it more power. You’re paying attention to it in a very particular way where you’re saying “Hey, I hate you. I don’t want you in my life anymore,” and that feeling is still like, “But I exist,” and you’re like, “No no no, you don’t deserve to exist, get out of my house!” And that feeling is still like, “But… you haven’t actually addressed the problem at all whatsoever.” That can create all this tension, and then that tension just creates more pain, and so one of the best ways – this is something that, like you said, is addressed in different kinds of yoga practices and meditation – the most constructive way to give those those painful feelings less power is to do the opposite of what you think you should do, which is tell yourself that it’s totally okay to be experiencing it. To tell that pain or discomfort, “Just stay as long as you need to. I’m cool. Look, I can deal with this, this is fine.” That the way it gives painful feelings less power.

“This book is definitely the most personal thing I’ve ever published. I took more risks than I have in the past in order to be more honest and to really say what I was thinking.”

It creates more space for you to actually think about other things in your life. At the end of the book is is that sequence about letting go, and there’s a few images about calling up the heart, and inviting the heart over to tea. It sounds incredibly corny to say it like that. That sequence is definitely inspired by this Buddhist story that talks about how the Buddha dealt with his his enemy Mara, a demon king. Instead of trying to chase him away, he’d always acknowledge his presence, going so far as to invite him over for tea. Mara just kind of gets tired of bothering him and goes away.

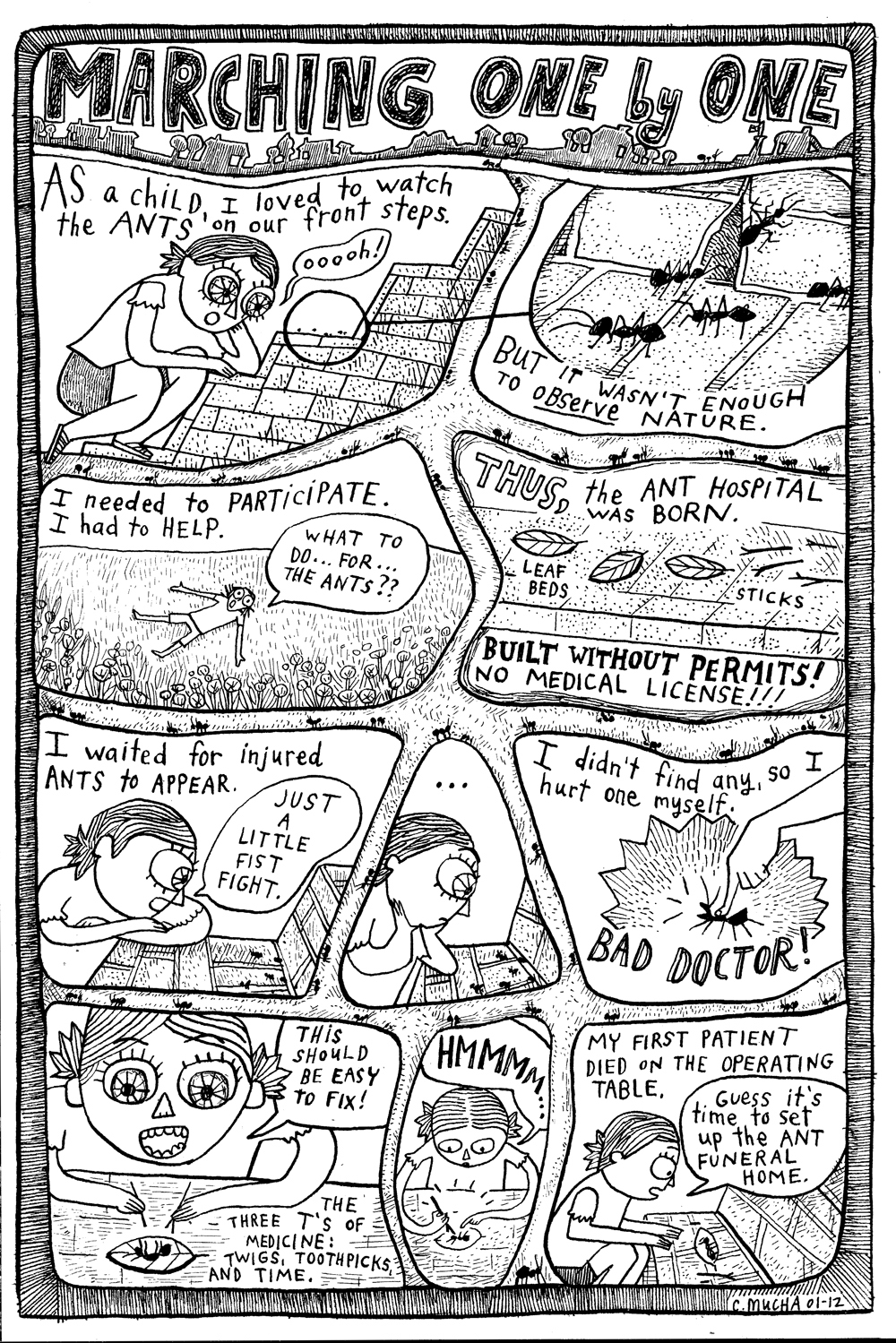

FS: A lot of your work take place during either childhood. What draws you to that period or that time?

CM: I’m really interested in stuff that happens as a kid because I had a very, very overactive imagination to the point where it caused a lot of problems for me.

Runner Runner #1 (2012), Tugboat Press

CM: I wrote a story about believing that witches lived in my closet. It was fun to combine things about being adult with those childhood memories. But that was a real thing that my family had to problem solve around. Like, “Okay, Corinne really believes that there are witches living in her closet who have huge needles that are going to stab her in the feet and then drag her to their castle in the middle of the night, so she won’t go upstairs by herself… She can’t sleep, how do we deal with that?” And I was really worried about being kidnapped, and I was really worried about alien invasions. I took normal kid anxiety but then was like, “Let’s take this to the NEXT level! I don’t think other kids are worrying about it quite enough, I’m going to make fear of alien abduction a real problem in my life! Yeah! Let’s strategize around THAT little worry.”

Papercutter #8 (2008), Tugboat Press

So I’m interested in those fictions that I created as a kid, to try to figure out why they felt so real. And then as an adult, I’m interested in other random fictions that I might create on a regular basis. Like seeing a dog in a striped sweater and believing for a few minutes that it is a “city zebra.” I might have more awareness of situations like that not being real, but I do wonder how could my life change if, for example, I choose to pretend that the animal living in the basement is a monkey as opposed to a cat that’s just roaming around the neighborhood. Of course I know there’s not a monkey in the basement, but what if I pretended that I actually thought that? What changes then? And I think what changes much of the time is you get to have a lot more nonsense conversations with people, which I always value.

FS: The day-to-day gets more interesting when you infuse it with that fun and fantasy.

CM: Yeah. It might make you appear like less of an adult, too. But that’s fine.

FS: Working with kids has to really bring that in on a regular basis, which must be fun.

CM: Oh yeah. That’s one of the biggest reasons that I love working with kids. They will take nonsense conversations very seriously. We can just start with a hypothetical situation and tease it out over the course of an hour until it becomes a business proposal. I also have a lot of adults in my life who are willing to spend time joking around and pretending not-real things could be real.

FS: Do you feel like you have found a comfortable place in the comics community?

CM: Yes! Though, you know, like anything else, it’s always changing. It hasn’t been that long that I really felt, like we were saying at the beginning, that I deserve to legitimately call myself a cartoonist. These days, I have more of a sense that I’m probably going to keep doing this for a while, and that maybe other people’s opinions matter less than I thought they did in the beginning. One of the benefits of making comics for a long time is just getting to know so many other cartoonists on more of a personal basis and just seeing they’re all just people too! (laughs) I see some people’s work and I’m just like, “Oh my god, you’re like a deity of some kind, this is amazing!” And then maybe you get to hang out with them a little bit and realize they struggle with art things just like you do. Sometimes. Maybe less. But nobody escapes the art curses!

Festival Season

Festival Season